Menu

The past, present and future

The ancestors of native Australian ducks survived the catastrophic event that destroyed most land living dinosaurs 65 million years ago, well before modern man existed. Over millions of years these nomadic birds adapted to the harsh Australian environment by breeding up in times of plenty and then dropping back in numbers during droughts. This natural cycle has ensured their survival for millions of years.

First Nation people respected Australian wildlife, lived in harmony with nature and never overexploited the natural environment.

But in 1788 Europeans arrived in Australia with their firearms, cats and rats and early European hunters also released foxes and rabbits into the environment for their shooting enjoyment. The impact of these introduced species on the fragile Australian fauna and flora continues to be nothing short of catastrophic.

Settlers believed the land required ‘conquering’ so native habitat was cleared, natural resources were exploited, waterways diverted and wetlands drained. As recently as the 1960s an Australian national motto was said to be: “if it moves, shoot it; if it doesn’t, chop it down”. Even today some duck shooters exhibit these words on their cars:

In the 1950s duck shooting was starting to become more organised under Premier Sir Henry Bolte, who was also a member of the shooting organisation Field and Game Australia.

The next Victorian Premier, Sir Rupert Hamer was also a duck shooter. Shooting ducks was regarded as a totally acceptable activity and up until the late 1980s guns were sold in K-mart and Myers. In the weeks leading up to shooting seasons multi-page lift-out supplements advertising everything relating to duck shooting were included in the main newspapers.

Native waterbirds were seen solely as targets to be shot and no one spared a thought for their suffering until Levy commenced his campaign in 1986. He challenged the 100,000 shooters at that time by taking 15 rescuers to one of the wetlands to rescue wounded birds.

Because of the large numbers of threatened Freckled Ducks recovered by rescuers each shooting season, the Waterfowl Identification Test (WIT) was introduced in 1990. It assessed whether shooters could tell one species from another and was intended to reduce the numbers of Freckled ducks shot.

However, shooters are only required to pass the WIT once, when applying for their first game licence. Even the regulatory body, the Game Management Authority (GMA) apparently has little confidence in this test as evidenced by this GMA poster (right) found by rescuers at a Victorian wetland in 2015. Obviously there is a huge problem if the GMA believe that duck shooters might mistakenly identify enormous Brolgas, which stand over one metre high, for small native duck species. It is far more likely that the GMA are fully aware (as indeed CADS’ rescuers are) that many duck shooters are likely to target anything and everything.

Every year rescuers recover protected and threatened species which have been illegally shot by duck shooters. They either can’t distinguish between different species or they simply don’t care what they’re shooting.

The Freckled Duck (Stictonetta naevosa) is endemic to Australia and is considered to be an ancestral species (Frith 1982). It is the only member of its genus and is classified as endangered in the October 2021 Flora & Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 – Threatened List. In 2014 BirdLife Australia estimated there were only around 20,000 Freckled Ducks in Australia.

These protected birds move from the mainland to subcoastal wetlands in dry periods, congregating in flocks which give the impression that they are more common than they actually are. They are frequently shot illegally by duck shooters who even want the species added to the so-called ‘game’ list.

The following are examples of some of the illegal incidents that took place on just a handful of Victorian wetlands yet there are roughly 20,000 waterways where duck shooting can take place for three months annually. CADS’ rescuers can only cover a few wetlands, so the other massacres which would undoubtedly have taken place, go undocumented.

Prior to the duck shooting season in 1993, 300 Freckled Ducks were sighted at the northern end of Lake Buloke. The Conservation Department closed the northern end where the Freckled Ducks had been seen. Levy informed them that when the guns went off the Freckled Ducks would take fright and fly out of the sanctuary and into the guns on other parts of the wetland. This is precisely what happened. 272 illegally shot Freckled Ducks were recovered by rescuers.

In 2013 CADS received a tip-off on the opening weekend that a massacre of native waterbirds had taken place at Box Flat, a wetland close to the regional town of Boort. Over 2,000 native waterbirds were massacred including some 200 threatened Freckled Ducks. A Senior Director of the Game Management Authority was informed that a massacre was likely, but did nothing.

The following was reported in The Age, 13 May, 2013 in an article titled ‘Hunter warned of bird massacre’

“But a Fairfax Media investigation can reveal that the shooting spree – the likes of which Victorian authorities have not seen since the early 1990s – could have been prevented. Days before the incident, government officials were tipped off by a concerned hunter with a warning.

This hunter, acting as an informant, told a Department of Sustainability and Environment official that Box Flat should be watched on the duck season opening weekend. Only a year before, in an incident never reported, trigger-happy shooters had gone to the remote wetland and shot birds indiscriminately.

The shooters had ‘‘shot the shit out of the joint, shot everything that moved’’, the informant told the department. There was talk, the hunter added, that it would happen again.

But Game Victoria, the government body in charge of the duck season, said that while the tipoff was judged to have ‘‘something in it’’, the authority prioritised potential protester activity on the Saturday morning at nearby Woolshed Swamp. But compliance officers found no protesters there.”

Together with the unreported massacre at Box Flat in 2012, it was also alleged that a similar massacre had taken place at Woolshed Swamp which was also covered up by the Department.

Rescuers recovered 42 illegally shot threatened Freckled Ducks in the first week of the 2014 duck shooting season from Bullrush Swamp south of the Grampians. 100 illegally shot Freckled Ducks were recovered that season from wetlands near Kerang and from several other wetlands around Victoria.

Due to large numbers of waterbirds on the Koorangie Marshes in 2017, including threatened Freckled and Blue-billed Ducks, CADS unsuccessfully pushed for this wetland to be closed to shooting. On the opening of the duck shooting season a barrage of shooting started 20 minutes early, and during the weekend rescuers recovered 183 illegally shot threatened species including 145 dead or wounded Freckled Ducks and 296 protected birds.

Clearly the WIT fails to protect birds from being shot.

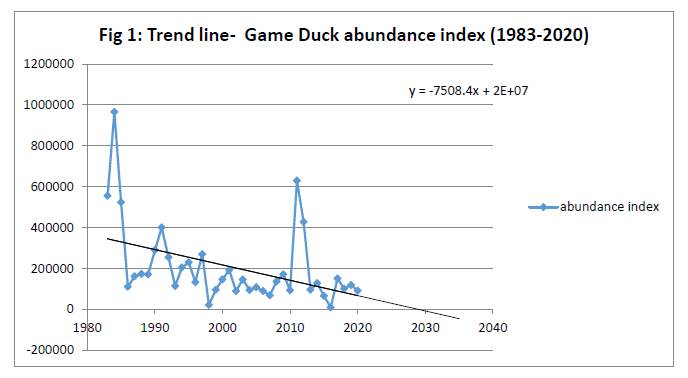

Since 1983, Professor Richard Kingsford from the University of NSW has conducted annual aerial surveys of waterbirds across eastern Australia. Waterbird numbers have been declining steadily over this time and in 2016 he used the analogy of a bouncing ball, saying the resurgence will be less like a super ball that recovers almost to the height it was dropped but rather that of a tennis ball with its rapidly diminishing rebound.

While native waterbirds have survived for millions of years, the trend line in the graph below shows how Kingsford’s statistics indicate they are facing a very serious decline.

The appalling cruelty our waterbirds face at the hands of duck shooters is one thing, but the world is on the brink of another extinction event with many species currently extinct or facing extinction. To continue to pander to the shooters and allow the recreational shooting of our precious native waterbirds at this crucial time is monumentally irresponsible.